Modular software architecture¶

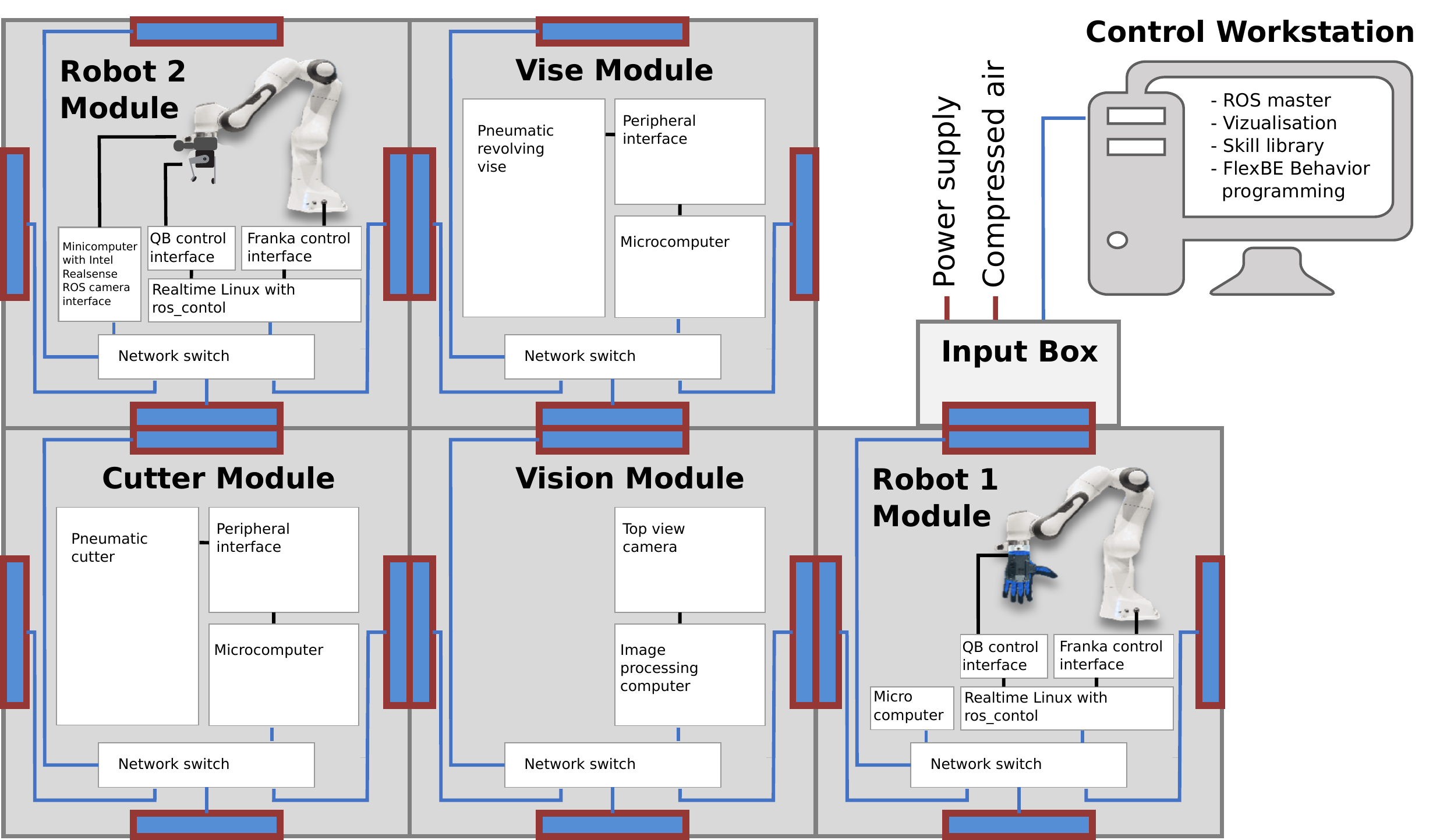

To facilitate the implementation of modular reconfigurable workcells, we developed a software architecture that reflects hardware modularity and enables plug-and-produce connectivity within the workcell. As the backbone, Robot Operating System (ROS) is used. It provides standardized interfaces to robots, sensors, grippers, and peripheral hardware elements and enables plug-and-produce connectivity and communication within the cell. Furthermore, toolchains for quick and efficient setup and programming on the workcell (task-level programming based on FlexBE, skill specification and workcell calibration by kinesthetic teaching) are integrated into the overall software architecture.

The proposed design enables that the cell’s functionalities can be expanded without disrupting the existing software architecture. This is supported by making use of Docker containers for the integration of new software modules. In the Docker containers, new modules can be deployed with all the necessary libraries without causing conflicts with any preexisting software packages. Developers can thus integrate new software without the need to reprogram any of the existing modules, which also eases the deployment of new hardware in the cell.

ROS backbone¶

The purpose of the software architecture is to define all the constituent modules and ensure connectivity between them in the context of data flow. While several software frameworks exist, the Robot Operating System (ROS) provides the most widely used framework for the development of robotic software architectures where components exchange data over the shared network. Various tools and features that are available within ROS contribute to realizing the pursued software reconfigurability of the cell. In our case, software modularity and reconfigurability mean that it is possible to expand or adapt the cell’s functionalities without disrupting the existing software architecture. It should be possible to develop new software components without the need to reprogram any of the existing ROS nodes. This also eases the development and integration of new hardware components with their own ROS nodes.

Of the many features and tools provided within ROS, we use the following ones to achieve a high degree of software modularity in our system:

nodes - any program that has connectivity to the ROS network and can therefore access to and publish data across it (i.e. low-level hardware drivers, high-level state machines, trajectory generation, etc.)

topics - a publish/subscribe table advertised by each ROS node that defines the data that can be provided by the said node, e.g. robot joint states, force-torque sensor data, state of the cutter, etc.

messages - a predefined structure to encapsulate data to be transferred across the ROS network for other nodes to read, e.g. robot joint states are written into sensor_msgs/JointStates, which is a predefined ROS message structure that can be sent across the ROS network.

parameter server - used to store various static configuration parameters, e.g. controller gains, camera exposure parameters, kinematic models, etc.

services - a request/response based Remote Procedure Call (RPC) interface that a node can expose in order to trigger short-running tasks that do not require preemption or monitoring from within the ROS network, e.g. visual quality control, pneumatic gripper actuation, tool exchange system lock/unlock, gravity compensation mode toggle, etc.

action servers – similarly to the services, a request/response RPC exposed by a node. They are, however, used to trigger long-running preemptable tasks from within the ROS network that provide feedback throughout their execution, e.g. robot movement tasks, servo gripper grasping tasks, flexible fixture reconfiguration, etc. \end{itemize}

In this architecture, each module is connected to the same network in order to broadcast its data and receive information and instructions about what action to perform at any given time. Apart from ensuring software reconfigurability, the proposed architecture allows us to control and monitor all the different modules in the cell as well as the workcell as a whole. The system is designed in such a way that each module connects directly to the ROS network. This way we ensure that the data is structured and parsable by all of the software components within the developed system.

An important feature of the proposed architecture is that we can program and exchange information between heterogeneous hardware modules within a single software architecture. Once the developer integrates a new module into ROS, the workcell programmer needs to know only which functionalities the new module exposes to ROS. No special knowledge about hardware-specific software is needed to start programming new workcell applications.

Containerisation¶

Although ROS provides a good framework for the development of robotic workcells, setting it up on a single computer still takes some effort and time. Our system is composed of several modules, each with their own computer. Setting up ROS and maintaining all of them would be very time-consuming. Moreover, the transfer of ROS code from one machine to another can be rather difficult. To address these two issues, we decided to base our development process and overall system on Docker containers.

A Docker container is an isolated environment that is built from a Dockerfile. In this file, we specify which software distribution the container is based on and what types of dependencies should be installed. The main advantage of this approach is that unlike virtual machines, Docker containers do not emulate the host’s hardware but share it. This in turn means that, compared to a virtual machine, a Docker container uses fewer resources. Additionally, once the \texttt{Dockerfile} has been written, the image that is built from it will be the same regardless of the platform it runs on. In terms of deploying ROS software on different modules, this means that the developer designs the code in such a way that it runs within the Docker container and thus removes the commonly encountered problem of unmet software dependencies when transferring the code.

In terms of network connectivity, Docker containers can communicate between each other just like any other programs, including ROS nodes. This means that different software components running in different Docker containers can exchange data seamlessly.

Integration of robot manipulators¶

The archetypical workcell module can be upgraded to integrate various robot manipulators in the workcell. The software of such a module is based on the ros_control framework, which provides a hardware abstraction layer (RobotHW) that enables standardized access to actuators and comes with a common interface (ControllerBase) to write robot-agnostic controllers.

In our software stack, we provide various trajectory generation algorithms. To enable interaction with these plugins, we provided a separate ROS action server wrapper for each of the motion generators. Whenever a new movement request (an action goal in ROS terminology) arrives to a specific action server, the underlying motion generator plugin generates either a joint or Cartesian space trajectory. The trajectory points are processed in a parallel real-time safe thread, running at 1 kHZ. In this thread, we rely on joint and Cartesian impedance control to calculate the desired joint torques. Finally, the calculated torques are sent to the low-level robot controller via RobotHW interface.

The main benefit of using ROS action servers to trigger robot motion is the ability to cancel the request during execution and to get periodic feedback about how the request is progressing. Upon acceptance, the action goal’s status is set to active if there are no other action goals, e.g. motions, waiting for execution. If the action goal is preempted, the robot does not immediately enter an emergency state and does not require any restart procedure. The client receives appropriate result messages in order to handle the preemption in its scheme and continue with another action if required/possible. This approach also enables the integration with state machine frameworks for behavior level programming, such as for example FlexBE, or integration with different motion planning software stacks such as the widely adopted MoveIt!

In the reference system, we use Franka Emika Robot and manufacturer provided franka_ros package, that provides ros_control integration and custom torque controllers.

Integration of peripheral devices¶

To support disassembly processes in the ReconCycle cell, various peripheral devices are integrated alongside robot manipulation capabilities. For example, the robot module must be able to activate or deactivate the pneumatic tool changer mounted on top of the robot. Devices such as clamps or cutters require activation signals and state checks. We use Raspberry Pi 4 as the standard microcomputer. It provides control signals and reads sensor values by connecting peripheral devices to its GPIOs. Each GPIO must be properly configured using a suitable software library.

For global control and synchronization of peripheral equipment, we developed a ROS package that wraps the software library for configuring and controlling GPIOs. This allows configuration and control of peripheral devices through ROS services, eliminating the need for direct GPIO management. It consists of:

Equipment Server: Configures GPIOs based on the module’s configuration file and forwards control commands from ROS services to the connected equipment.

Equipment Manager: Allows modification of the module’s configuration file via a ROS service.

To ease configuration management, we developed a ROS package with a user-friendly interface for handling configuration files. The interface communicates with the Equipment Manager, guiding the user through creating or modifying configuration files. For simplified deployment, the ROS package is packed into a Docker container.

Task-level programming¶

Due to a well-developed graphical user interface, FlexBE framework has been employed in the ReconCycle project to facilitate the creation of complex robot behaviors for disassembly tasks without manual coding. This section provides an overview of FlexBE states and behaviors. Each state represents a specific action or step in a robot’s behavior. Behaviors in the FlexBE frame-work are essentially state machines, meaning that behaviors are constructed by connecting individual states through transitions.

We have prepared corresponding FlexBE states for executing robot trajectories, controlling peripheral machinery, manipulating process data, etc., including:

executing robot motions (in Cartesian or joint space),

reading from and writing to the skill library (e.g., storing data acquired by kinesthetic teaching and initializing desired robot movements),

triggering functionalities on peripheral devices (e.g., moving pneumatic grippers, vise, cutter) and operating the CNC milling machine,

performing tool-changing process,

obtaining results from the vision processing pipeline, including semantic scene analysis and action prediction.

Development of new skills¶

New skills (robot operations, vision tasks, pneumatic control, …) can be developed using available templates and existing skill scripts. This allows the user to tailor the workcell operation to their specific tasks and requirements. More details on skills and their development are available in the Manual section of the documentation.

Helping tools¶

A number of tools that facilitate fast and simple workflow programming have been developed, including automatic URDF files generation from STEP models, automatic FlexBE state generation using Jinja templating, and a tool for kinesthetic guidance, which allows storing robot poses and motions into a database.